Weird, Wild and Scary Weather Events Explained

January 2015 - The Case of the Snowless Snowmobiles

In January 2015, the Seven Clans International 500-Mile Snowmobile Race from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to Wilmar, Minnesota, was called off because there was no snow on the ground. The race, with 350 to 400 entrants, dates from the 1960s. This was not the first time that lack of snow was a problem. The event was canceled for 2 years in the 1980s. Race director Brian Nelson said, “If anything, there will be more enthusiasm for it next year.”

Despite the enthusiasm, the snow stayed away and the 2016 race was also canceled. El Niño, the warm Pacific Ocean current, reduced snowfall in both winters.

March 2015 - The Case of the Missing Storms

The national Storm Prediction Center (SPC) regularly posts an online map showing all thunderstorm and tornado watches across the continental United States. From March 1 to 24, 2015, the map was blank. This was the first time that this had happened in the 45 years that the SPC had been keeping records. Although March is not normally a big month for tornadoes, an average of 78 twisters touch down in the month.

Experts believe that abnormally cold, dry weather in the central United States prevented any outbreaks in March of that year.

February 2015 - The Case of the Milky Rain

On February 6, 2015, people in parts of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho found their cars and windows covered with a grayish powder left by a rainstorm. Meteorologists who collected the rain noted that it was “milky” in color and that it might contain ash from volcanoes in Russia or Mexico.

This didn’t make sense to other scientists. The volcanoes were thousands of miles away, and the wind that brought the milky rain had come from a different direction. Closer analysis showed that it was high in sodium, the main element in salt. This led investigators to Oregon’s Summer Lake, a shallow body of water that often dries up during droughts.

The night before the mysterious rain, Summer Lake had winds of up to 60 miles per hour, strong enough to lift a cloud of sodium- rich dust into the atmosphere and carry it 480 miles to the affected region.

April 2021 - The Case of the Swarming Storms

In 2011, 303 tornado warnings were issued on one day, April 27, when a combination of moisture from recent thunderstorms, warm air from Mexico, and cold air from Canada created ideal conditions for tornadoes in the central and southern United States, especially Alabama and Mississippi.

Later, some scientists suggested that smoke from huge fires in Central America might also have played a part in the situation, which produced one of the largest, costliest, and deadliest tornado outbreaks in U.S. history. The fires’ black soot drifted northeast and settled over the southern United States, trapping the Sun’s heat and creating wind patterns that often produce tornadoes.

May 1780 - The Case of the Dark Day

In the midday hours of May 19, 1780, night birds began to sing and people had to light candles in order to work and do chores. Some frightened folks thought that it was the end of the world. Although the darkness was deepest in Maine and northeast Massachusetts, as far south as New Jersey, Gen. George Washington reported in his diary seeing dark clouds “and at the same time a bright and reddish light intermixed with them, brightening and darkening alternately.”

The event came to be known as New England’s “Dark Day.”

Since then, scientists have proved that the darkness was caused by smoke from burning forests in Canada. The crucial evidence came from charcoal found in tree rings dating to that month in 1780.

June 1816 - The Case of the Disappearing Summer

Six inches of snow in Vermont in June is unusual, but not unheard of. Usually it melts and is forgotten. But in 1816, the cold weather lasted all summer. Frosts killed crops, and people—and animals—went hungry. Many Vermonters gave up on New England and moved west and south to warmer areas.

Scientists think that the unusually cold weather was caused by an event that happened a year earlier on the other side of the world—the eruption of Mt. Tambora, in what is now Indonesia. The huge explosion shot enough ashes and dust into the atmosphere to put the entire Northern Hemisphere into the shade. The period is now famously known as “The Year Without a Summer.”

July 1843 - The Case of the Flying Alligator

“The beast had a look of wonder and bewilderment about him, that showed plainly enough he must have gone through a remarkable experience.” So reported the editor of the Charleston Mercury of a 2-foot-long alligator found at the corner of Wentworth and Anson streets on the morning after a terrible thunderstorm that rocked the South Carolina city on July 1, 1843.

Small animals falling like rain have been reported for hundreds of years. Most experts believe that the creatures are sucked into the sky by strong updrafts of wind or even tornadic waterspouts that form over oceans and lakes and then carry them long distances before they fall to Earth.

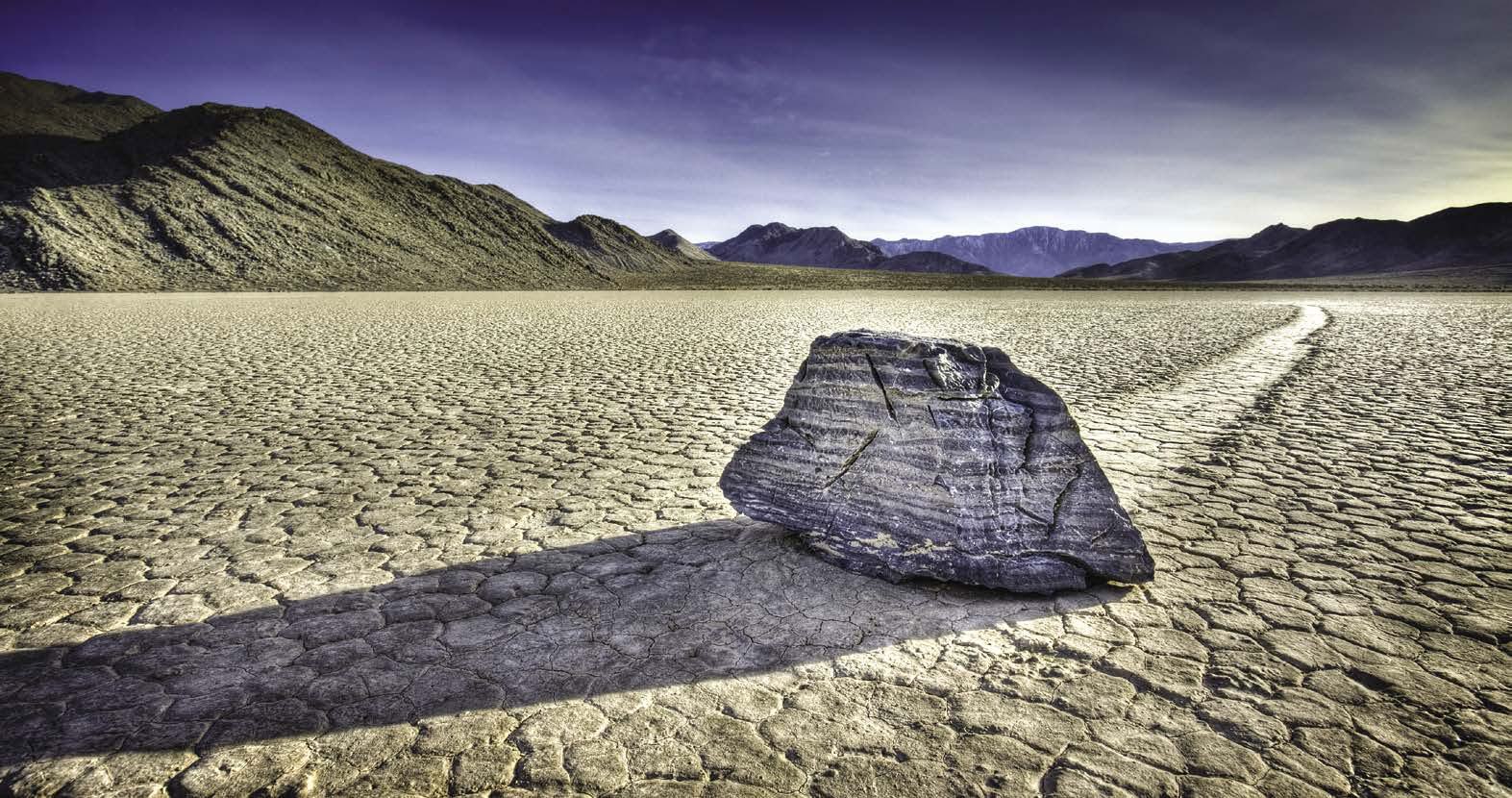

August 2014 - The Case of the Sliding Stones

A part of California’s Death Valley is called Racetrack Playa (playa is Spanish for “beach”) because of the mysterious tracks in the sand left by large, heavy stones.

Scientists solved the mystery in August 2014, after having witnessed stones being moved hundreds of feet across the desert in 2013 and 2014. The sliding stones are embedded in or pushed by thin sheets of ice that in turn are propelled by the wind along an even thinner layer of meltwater. The combination of ice, water, and mud is slippery enough to allow even heavy stones to move in light winds. The ice forms because in Death Valley nighttime temperatures can fall below freezing.

September 1995 - The Case of the Monster Wave

The navigation bridge of the Queen Elizabeth 2 stands about 100 feet above the surface of the sea. So imagine how Captain Ronald Warwick felt at 4:00 a.m. on September 11, 1995, when he saw dead ahead a wave whose crest was at his eye level. “It looked as though the ship was heading straight for the White Cliffs of Dover [England],” he said.

He had already altered course to avoid Hurricane Luis, which was creating winds of 130 miles per hour and kicking up enormous waves. But the monster he saw before him was no ordinary wave, and his ship was about to hit it.

“An incredible shudder went through the ship, followed a few minutes later by two smaller shudders. There seemed to be two waves in succession as the ship fell into the ‘hole’ behind the first one,” he reported. “The second wave crashed over the foredeck, carrying away the forward whistle mast.”

The monster was a “rogue wave,” produced by the multiplying effect of many waves in perfect synchronization. Fortunately, damage to the ship was slight and no passengers or crew were injured.

October 1962 - The Case of the Wildest Winds

It’s hard to say exactly how strong the winds of the 1962 Columbus Day Storm were. On this day, October 12, the weather station in Corvallis, Oregon, measured a gust of 127 mph just before the anemometer (the instrument for measuring wind speed)—and the tower it was attached to—was blown down and destroyed. Also blown down were countless trees, many of which were more than 1,000 years old. Buildings suffered, too: Of the 4,000 structures in the town of Lake Oswego alone, 70 percent were damaged.

The unusual storm developed when the remnants of Typhoon Freda combined with a powerful storm off northern California and raced northward with little warning. Scientists called it an “extratropical cyclone,” meaning a hurricanelike storm that develops outside the tropic zones. In the Pacific Northwest, survivors just called it the Big Blow.

November 1933 - The Case of the Black Blizzards

On November 11, 1933, high winds blew an enormous cloud of dust into the atmosphere, obscuring the Sun and burying farms in the Great Plains under as much as 6 feet of loose dust. The dust blew from South Dakota to New England, where it turned snowflakes red.

Eventually, 100 million acres of farmland were affected, and hundreds of thousands of farmers had to move out of the area.

Most historians date the beginning of the Dust Bowl to this day. Scientists believe that it may have been directly caused by changes in ocean currents in the Pacific Ocean, but it was also due to overcultivation, new technology (mechanical tractors and harvesters), and a misunderstanding of the limits of natural resources like topsoil and water.

December 2008 - The Case of the Shattering Trees

On the night of December 10–11, 2008, millions of people in New England were awakened by the terrifying explosive crash of tree limbs breaking and falling, the boom of whole trees toppling, and the thunder of heavy chunks of ice smashing into and cascading onto their roofs.

Everything was coated with ½ to 1 inch of ice. The trees, and miles of power lines, were brought down by the weight of it. Households were robbed of electric power for up to 2 weeks, and many schools were closed until January 2009.

A rare combination of unusual warmth the day before, a sudden invasion of freezing or below-freezing air from Canada, and a strong moist airflow from the south had caused heavy rain that coated every surface and froze.